Lesson One

A Case of Confused Identity

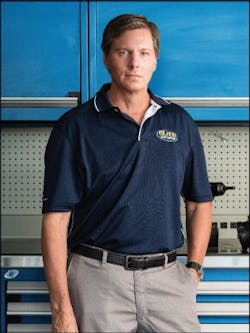

How David Schultz repaired his shop’s disjointed brand to help build a stronger reputation

“What’s in a name?” David Schultz jokingly asks himself, thinking back on his shop’s tumultuous 15 years of operations. “A whole heck of a lot, I guess.”

And Schultz crafted his business’s name very carefully. He weighed branding options, connected to business partners and inundated his market with advertising pieces.

By the time he sold Elite Collision Center to a consolidator in 2011, the brand was a local, Tempe, Ariz. staple.

No, you read that right. The business Schultz poured his effort into was his now-sold collision repair shop. His mechanical business—which operated next door, literally in the collision shop’s shadow—was simply an afterthought.

“When we built a facility [for Elite Collision Center] at our location about 15 years ago, there was a mechanical shop there and I bought it with the land,” he explains. “We changed the name to Elite Auto Repair, and ran it as basically a feeder for our collision business. It was never anything but a break-even side business.”

And it never established itself, at least in customers’ minds, as a separate business.

“Everyone just thought our collision business performed [the mechanical] work we did,” he says.

As the collision industry became increasingly difficult to turn a profit in, Schultz was presented with a generous offer for the business. With a mechanical shop still under his control, he decided to take the money from the body shop and invest heavily in transforming the service center.

Roughly 12 years behind on his marketing, Schultz determined that becoming a NAPA franchise would be his best route. He spent a year overhauling the shop’s appearance, changing out equipment and completely rebranding his marketing strategies.

“And we struggled to get any sort of a consistent customer base,” he says. “There was no reason for anyone to give us a try aside from a deal. They didn’t know us, they didn’t see us as an independent shop. We were just sort of another chain.”

Sales were “so-so,” Schultz says, hovering around an $800,000-per-year pace. And the shop fought a negative reputation brought on from other NAPA centers in the area.

In 2012, Schultz decided the shop needed another makeover.

“The biggest thing an independent shop has going for it is its longevity in the area, its branding and its connection with customers,” he says. “We needed to create that for the shop.”

Elite Auto Repair

Tempe, Ariz.

Size: 7,000 square feet

Staff: 11 (5 techs, 1 general manager, 1 service writer, 1 outside sales person, 1 bookkeeper, 1 porter and Schultz)

Average Monthly Car Count: 280

Annual Revenue: $1 million

Schultz decided to go back to the Elite Auto Repair name, repaint the shop and put in new signage. He wanted to give the shop a “one-off look” that ensured customers it was not a franchise. He put in custom artwork that included furniture made out of old road signs by an artist in New York.

He also entirely redid the business’s marketing approach. They began targeting customer demographics (looking for middle-class families with vehicles out of warranty) with direct mail, joining “conquest” mailer programs, adopting customer acquisition and retention systems from Demandforce and Constant Contact, and even utilizing a turn-key mobile application service that provided the shop an app-based customer rewards system.

In all, Schultz guesses he spent $30,000 in the rebranding effort. And it quickly paid off. With the new brand hitting its stride, sales rose 20 percent over a 12-month period ending in mid-2014. Schultz expects it to continue to rise, and he credits it all to his new brand.

“You need to spend time on your branding and time figuring out who you’re going to be,” he says. “And you have to push that to people, you have to get that out there in your community and show everyone who you are. People need to know that name, and have a connection to it. The name is everything.”

Lesson Two

Self Doubt, Business Basics, and a Bad Partnership

How Erin Rodriguez fired her partner to save her family’s business

She couldn’t do it, at least not on her own. She’d be taken advantage of by hard-talking customers, disrespected by vendors. It would be hard for people to take her seriously without having a real “expert” working with her.

That’s what Erin Rodriguez was told when she wanted to take over her father’s shop. She heard it from everyone, even her father.

“He’s very old-school Japanese and very into old-school roles for women, if you know what I mean,” Rodriguez says. “He wanted to sell the business to someone else, and I was pissed. I told him, ‘No way,’ and I bought the business outright from him.”

Rodriguez had spent nearly her entire life in her father’s Honolulu, Hawaii, shop, Pearl City Auto Works, a bustling 5,000-square-foot business that built its name on the strength of Rodriguez’s father’s reputation as a master of performance work. He worked exclusively in the back of the full-service shop, wrenching until the day he retired. Rodriguez was the one who handled all the bookkeeping and front-counter duties at the shop; always had, since she was 18.

“When I did buy it, though, I think I still had this self doubt that maybe my dad was right and it would be hard for me,” she says. “That’s what led me to my partner.”

He was a longtime technician at the shop. He was someone she trusted. And he wound up being the thing that nearly crippled the business and Rodriguez’s run as an owner.

Rodriguez wasn’t confident in her knowledge of vehicles, she says. She was worried that, as many warned her, customers would underestimate her and the shop’s abilities.

She let the technician buy into the business as a co-owner, and they’d partner in running the shop—Rodriguez handling the front counter, the former tech in charge of operations.

“And it was a disaster almost immediately,” she says. “I’ve never seen anyone get a big head in the way he did. He started coming in whenever he wanted, treating other techs poorly. It was a mess. Everyone in the shop was furious at him, and me for letting it happen.”

This was mid-2007 when the transition took place, and they had three other techs. All three threatened to quit. The shop, which had been stuck at a permanent $600,000 annual sales pace, was in chaos.

Pearl City Auto works

Pearl City, Honolulu, Hawaii

Size: 5,000 square feet

Staff: 6 (4 techs, 1 service writer and Rodriguez)

Average Monthly Car Count: 250

Annual Revenue: $1.2 million

There was no order, no organization, no workflow systems, no processes.

“Either the business was going under, or he was going,” Rodriguez says. “Basically, I fired him.”

Rodriguez forced a buyout. She took over the company, and for the first time, she felt like she had actual control. If the business was going to succeed or fail, she remembers thinking, she wanted to do it her way.

She refocused the company’s vision: As other area shops were weighed down by circumstances related to the recession, she reinvested in her business. She used the shop’s minimal cash flow to purchase the latest scan tools, update subscriptions and offer training to her team. She began working with a business coach and taking management training.

Not only did the commitment to the business’s future win over her team, it dramatically altered the business. Maintaining similar car count totals, annual sales hit $1.2 million in 2013.

“The biggest thing is that I feel like I proved I could do it,” she says. “I had a picture of what this business could be, but I let doubt get the best of it. Now we know who we are as a company and where we’re going.”

Lesson Three

It’s How, Not How Many

How Jason Dickerson turned a chaotic, busy shop into a true money maker

If everything in a repair shop is set up properly, the main responsibility of a shop owner rests on one single task: getting cars in the bays.

Car count is crucial, obviously, and it’s the one aspect of the business Jason Dickerson has never struggled with; not when he was a technician operating after hours out of his home garage, not when he opened his first two-bay facility in the back of a service station, and not today, in his 2,000-square-foot shop.

“I’ve always been loyal to my customers, and they’ve always been loyal to me,” Dickerson says with pride. “Getting people in my shop has never been the problem.”

Yet, in early 2011, just about six years into running Dickerson’s Service Center, Dickerson still had nothing to show for his business’s popularity in the Creedmoor, N.C., area. At 250 jobs per month, car count pushed the shop to its limit. But it was the $150 average repair order (ARO) that nearly pushed Dickerson to his.

Now, go all the way back to that first sentence, and focus on that if.

“That’s the big part of it,” Dickerson says. “There are so many things that go into being successful beyond just getting cars to work on. I didn’t know any of it. I didn’t know about margins or about benchmarks or pricing properly. The only thing I knew was whether or not at the end of the month I had enough to pay my bills—and it was a worry every month whether or not I would.”

Dickerson refused to push forward at the status quo. He needed to drastically alter the way the business operated, or get out. He opted for the former.

“You don’t know what you don’t know,” he says. “I needed to figure out what I was doing wrong, and I needed to fix it.”

Dickerson’s Service Center

Creedmoor, N.C.

Size: 2,000 square feet

Staff: 5 (3 techs, 1 service writer and Dickerson)

Average Monthly Car Count: 250

Annual Revenue: $960,000

Dickerson began signing up for local management training and looking for as many educational opportunities as possible. He joined a program through Management Success! and slowly began to get a better grip on his business.

Gross profit—something he knew nothing about before training—hovered below 30 percent when he first began measuring in fall of 2011. That November, sales barely topped $40,000.

Armed with a new perspective on how his business operates, Dickerson began focusing on his numbers, and finding ways to improve them. He put in a new parts-pricing matrix that allowed him to earn higher margins on lower-priced products and lower margins on higher ones. And, realizing he wasn’t getting enough out of each vehicle that came in, he had his team inspect each car that came in the shop through a vehicle maintenance sheet that he and his techs created.

“It wasn’t about upselling,” he says. “The idea is that if they were going to be going on a road trip, it’s our responsibility to let them know exactly what their car needs. Educate them, then let them make the decision.

“I’ve always been focused on earning their trust, and making sure they see that we’re here to help them is a huge part of that.”

As his team went about its new inspection and informational selling strategies, the shop began to hone its operations. Organization in the shop improved, and Dickerson says that throughout 2012 and 2013, the business has slowly come into its own.

In June 2012, the shop topped $80,000 in sales, working on just fewer than 250 vehicles in what is traditionally one of its slowest months of the year. ARO was $319, gross profit topped 60 percent, and Dickerson hopes to top $1 million in total sales for the year. He’s looking at moving into a bigger facility in the fall.

“It’s growing and growing the right way,” he says. “I’m trying to step back and focus on the big picture. Everything is getting in place, and really, the only thing I’ll have to worry about is keeping the cars coming in.”

About the Author

Bryce Evans

Bryce Evans is the vice president of content at 10 Missions Media, overseeing an award-winning team that produces FenderBender, Ratchet+Wrench and NOLN.